A Shelter for Art at the Dawn of the Proletariat

July 18, 2025

Editorial, Santiago, Interdependence

July 18, 2025

Editorial, Santiago, Interdependence

Electrified voices emerge from inside the house, as if an interview was being recorded. This is the headquarters of the community television channel Señal 3 of the La Victoria settlement, which broadcasts a daily program dedicated to the vicissitudes of the community. On the façade is a motto: “Communication at the service of the people.” The design of the building is what might be called “sui generis architecture”; a do-it-yourselfism that combines reinforced brick walls, an iron door, a wooden roof structure with a “tejado de una sola agua” (a shed roof), and a tin smoke outlet. This adaptation of a house into a television studio is in line with the history of the neighborhood. Located on the outskirts of Santiago, Chile, the land was taken over by residents in 1957.

That is not the only house that has been converted into a business. Down the road is another small house, this one converted into a church. Off in the distance, the barking of quiltros (street dogs), the chants of street vendors, the chopping of welding machines, and a mechanical hum can be heard. Further down is a house that has been converted into a hair salon. Syncopated melodies come out of a garage, but it’s not reggaeton. The graffiti next to the door reads: “I believe that cueca was invented by Satan.” Cueca is the most popular dance in Chile, and the garage is actually an urban cueca club, Bar Victoria. Cueca might not have been invented by Satan, but it was certainly promoted by Beelzebub: in 1979, the Pinochet dictatorship declared it the “national dance.”

Dictatorial traces in this working-class neighborhood are not only audible, they are also physical. While under the presidency of Salvador Allende (1970–73), this area was densified with the “Ahora Vamos p’Arriba” (“Let’s lift ourselves up now”) plan of the Urban Improvement Corporation (CORMU), which gave social housing to those who until then lived in informal camps. The implementation of Supreme Decree No. 420 of 1979, however, under the military regime (1973–90), deregulated urban land, privatized public spaces, and reorganized neighborhoods to favor speculation. This led to the expulsion of the lower socioeconomic stratum from areas of potential real estate interest. This is how the Pedro Aguirre Cerda neighborhood came about, whose residents occupied abandoned parks or soccer fields, from where they integrated services and businesses into the community. Self-construction is part of the history of this area.

On the corner, at 2941 Felix Mendelssohn Street, there is a zinc “tejado a dos aguas” (gable roof) warehouse. It was built in 1997, and like Bar Victoria, in the courtyard of a family home. Luis Alarcón and Ana María Saavedra built Galería Metropolitana in this working-class neighborhood as an act of hospitality.Managers, curators, and founders of the Gallery, Saavedra has studies in literature at the University of Concepción and the University of Chile, while Alarcón has studies in theory and history of art at the University of Chile. In the 1980s, two warehouses in the center of Santiago were used to host avant-garde musicals, theater pieces, and artistic events, which generated bubbles under the repression and censorship of the dictatorship: El Trolley and Matucana 19. Galería Metropolitana follows in this path, although far from the urban core and conceived during democracy, when the enemy was no longer the authoritarian and visible hand of a general, but the invisible hand of the market.

Chile has been called the “laboratory of neoliberalism,” an economic system implemented in the 1970s by a group of Chilean Milton Friedman groupies, the Chicago Boys. Their logic—extreme privatization and the erasure of public services—survived the democratic transition and continues today with its tyranny of profit. It is within this context that Alarcón and Saavedra decided to offer a free cultural space in the courtyard of their house. They call themselves a “gallery,” a term with commercial implications, but it is the antithesis of the white cube. In this metallic prism, art functions symbolically: as something non-functional and useless, in a neighborhood inhabited by workers, whose life is sustained by offering (at least) eight hours of their days to making money.

In the design of the warehouse, Alarcón and Saavedra took inspiration from external metallic structures and elements present in their neighborhood: spaces dedicated to packing fruit, self-managed fast-food businesses, and the use of neon lights in night shops. Under the inverted “V” of its roof sits an orange neon sign announcing the name of the space.This follows the work of Gonzalo Díaz, one of the country’s most renowned artists, who placed the phrase “United in Glory and in Death” in neon on the front of the National Museum of Fine Arts for his 1997 exhibition. There is irony, co-optation, and anger in this; a mocking distance from the commercial art system and a solidarity towards the independent businesses in the neighborhood.

The warehouse hosts a tall, open, grey space. The floor is made of cement and the walls are made of zinc. Hundreds of Chilean and foreign artists have exhibited here since the late 1990s. Many liters of wine and beer have been drunk, as well as many nuts and empanadas eaten. Its openings are frequented by a small but enthusiastic group of regulars, as well as neighbors from the area of all ages, art students, people who have never set foot in a museum, foreign curators that land like astronauts, and academics alike.

A recent exhibition by architect Claudia Oliva, “Ni tan abandonado” (“Not so abandoned”), features images, sounds, archival materials, and a 1:100 scale model of the nearby abandoned hospital of Ochagavía. The construction of the medical center was started by the Allende government and was meant to be the largest hospital in South America, but was stopped following the coup d’état in 1973. The hospital subsequently became a white elephant, a symbol of the detachment between politicians and the needs of the working classes. With the arrival of the new millennium, it became privatized and converted into a business logistics center; its presence in the landscape a reminder of the interrupted dreams of the proletariat.

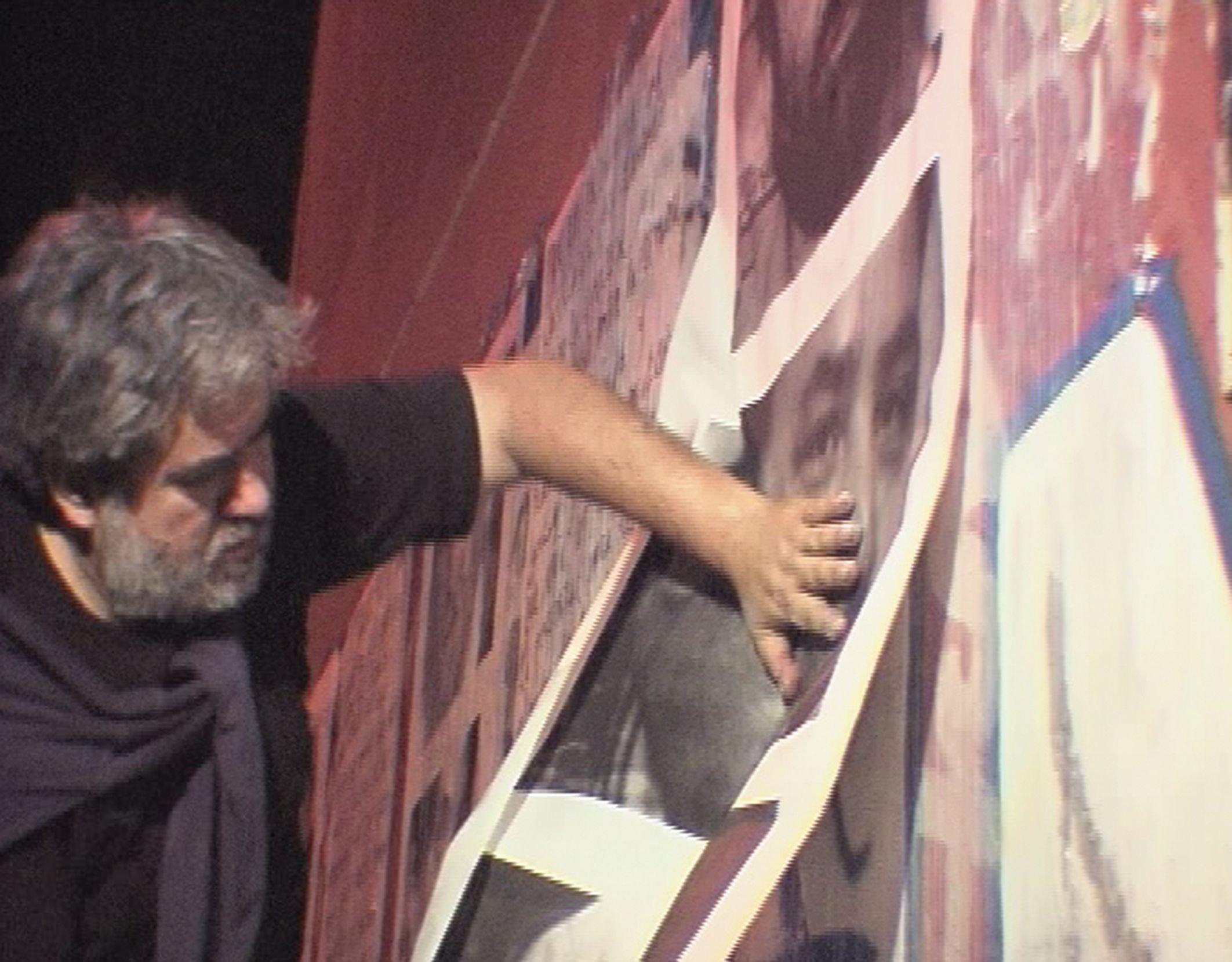

Ten years before this exhibition, “¿Cuál sueño? De la arquitectura estatal a la especulación inmobiliaria” (“What dream? From state architecture to real estate speculation”) similarly investigated the abandoned hospital, carrying out actions in front of its hulking ruins. And before that, for Juan Castillo’s 2001 “Geometría y misterio de barrio” (“Geometry and neighborhood mystery”), the artist lived in a house near the gallery and asked forty neighbors about their dreams (either nocturnal or life-related). He created portraits of each neighbor, and posted them around the neighborhood, as well as projected them onto both the local soccer field and the ruins of the abandoned hospital.

One of the dreams projected onto the hospital was that of Cristián Valdivia: “I wake up at night after having dreamed that I am speaking in another language, another tongue, another dialect. I have been woken up by my wife, who tells me ‘you are now transmitting on another wavelength, in another language.’” As Chilean theorist and friend of Galería Metropolitana Nelly Richard states, “Art and night virtually give rise to this other language,” one in which the political is integrated with the domestic.Nelly Richard, “A propósito de geometría y misterio de barrio de Juan Castillo,” Universitas Humanística, no. 56, (June 2003): 113. Jacques Rancière similarly philosophized about the anxieties the Parisian proletariat in the mid-nineteenth century, claiming that the role of dreams was “not to acquire knowledge of his condition, but to maintain the passions, the desires for another world that the constraints of work continually flatten to the level of mere instinct for subsistence that makes the proletarian, overwhelmed by work and sleep, the complicit servant of the rich, bloated with selfishness and idleness.”Jacques Rancière, La noche de los proletarios: Archivos del sueño obrero, trans. Enrique Biondini et. al (Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón, 2017) 49. Translation author’s own.

The dreams and nightmares of today’s Chilean worker are affected by the ravages of neoliberalism, which tells us since birth that competitiveness and individualism lead to success. Galería Metropolitana has been a champion of collectivism and shared responsibility, hosting many projects over the years that integrate neighbors as co-creators. For instance, the 2008 “Colección vecinal” (“Neighborhood Collection”) project, was conceived by the curator and artist Gonzalo Pedraza, and organized with two neighbors from the area. The exhibition was based on works loaned by the inhabitants of nearby houses. The walls of the gallery were covered with hundreds of paintings, images with a value more sentimental than artistic, which brought together family stories, victories, failures, moments of happiness, and memories of pain.

The question of the value of art hangs heavy over the roof of Galería Metropolitana, as well as the distinction between popular and elitist.“Perhaps this is the only place from which one could read the populist acrobatics of bringing highbrow art, the axiomatic reflection of the visual concept or the labyrinthine folds of complex thinking, to the neighborhood bastardization of a harsh commune,” wrote Pedro Lemebel about the gallery. Pedro Lemebel, “Aires de arte en la periferia,” in Galería Metropolitana, 1998–2004 …, ed. Luis Alarcón and Ana María Saavedra (Santiago: Ocho Libros, 2004), 10. In 2010, the Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn made his own version of Gabriel Orozco’s famous La DS (1993). Yet unlike Orozco, where the popular and the elite remain in balance, with Hirschhorn, the former subsumes the latter. In Chilean street slang, there is the concept of an “objeto hechizo” (“bewitched object”). Something is “hechizo” because it has been made with precarious elements and is meant to have a short lifespan. Hirschhorn planted a “bewitched” Ford Ranger double-cab pickup truck in the gallery, then asked two local mechanics to split it in half and glue it back together with industrial cellophane tape.

Perhaps Galería Metropolitana is a “bewitched museum,” a place that proposes another time, another space, in a “bewitched neighborhood.” Alarcón and Saavedra call it a “dislocated center.” It is a place that calls itself a gallery, but no art is sold. Galería Metropolitana is a halfway house for art and the public to reacquaint themselves with each other and learn to interact in a different way.

Interdependence (2022–2025) is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and OtherNetwork