Art Organizing as a Rhizomatic Practice

July 31, 2025

Editorial, Hanoi, Interdependence

July 31, 2025

Editorial, Hanoi, Interdependence

Founded in 2014 in Hanoi, Heritage Art Space (HAS) is among the longest-running independent art spaces in Vietnam since the emergence of the country’s contemporary art scene in the 1990s.Historical research on contemporary art in Vietnam often takes the 1990s as the starting point owing to the relative volume of unprecedented artistic forms that not only got featured in international exhibitions but also provoked opposing domestic responses. For a more detailed account of the beginnings of contemporary art in Vietnam, see Nora A. Taylor and Pamela N. Corey, “Đổi Mới and the Globalization of Vietnamese Art,” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 14, no. 1 (2019): 1–34. Typical of a cross-disciplinary contemporary art space, it has hosted exhibitions, performances, workshops, film screenings, and seminars. What sets HAS apart, however, is its sustained commitment to ambitious endeavors not commonly found in an artist- or curator-led initiative without long-term backing by the state or private patrons. These include an annual international residency program, a growing library with a diverse collection of domestic and foreign publications on art and culture, and a database on Vietnamese contemporary art.

To understand the significance of HAS’s work, it’s important to situate it within the broader context of Vietnam’s formal art education and institutional landscape. National art schools in Vietnam still more or less follow the same curricula that is rooted in the French colonial period, focusing on mediums of oil, silk, lacquer painting, and sculptureContemporary forms such as installation and performance have shown up in national art schools in Vietnam, but often only in elective courses or workshops. One such instance dates back to 1995, when German artist Veronika Radulovic, then a visiting lecturer at the Vietnam University of Fine Arts, brought Singaporean artist Amanda Heng into her classroom to hold a performance art workshop. In recent years, some new public and private universities have been established with course offerings in contemporary art, such as Fulbright University Vietnam, with its first cohort having graduated in 2023, and VNU School of Interdisciplinary Sciences and Art, which admitted the first batch of contemporary art degree seekers in 2024.. Meanwhile, national museums largely privilege two dominant visual narratives: the Indochinese aesthetic of pastoral charm and demure femininity, and socialist-realist portrayals of war glory and the working class. Consequently, the domestic development of contemporary art takes place predominantly in independent spaces, which emerge to meet the desire for novel art forms and artistic concerns deemed subversive by the stateThe writer acknowledges that instances of contemporary art forms realizing in state-owned spaces exist, such as Trương Tân’s provocative paintings and multi-media installation at the Hanoi University of Fine Arts in 1992 and independent art spaces housed in national museums like Blue Space in the Ho Chi Minh City Museum of Fine Arts from 1997 to 2010 and Viet Art Center in the Vietnam University of Fine Arts from 2006 to 2013. It is beyond the scope of this essay to evaluate the impact of these instances in the development of contemporary art in Vietnam.. Historically, the survival of such spaces is fragile because they are subject to state policing and prevailing moral norms; the closure of Nhà Sàn Studio in 2011 following public backlash against some controversial performance art it hosted, is a telling example. Adverse economic conditions also pose significant challenges, as seen in the Factory Contemporary Arts Center’s indefinite suspension during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In Vietnam, HAS is not the oldest independent art space. Nevertheless, the evolving forms of its activities amid changing material conditions is revelatory of the complexities of art-making and audience-building to foster a resilient domestic art ecosystem in the fast-developing and liberalizing Vietnam.

The Question of Space

In accounts of the beginnings of Vietnamese contemporary art, two independent art spaces frequently show up: Salon Natasha, located at the private studio and home of artist Vũ Dân Tân and his researcher-curator wife Natalia (Natasha) Kraevskaia; and Nhà Sàn Studio, based at the family home of artist Nguyễn Mạnh Đức. These are two instances of long-standing artist- or curator-led spaces tied to a specific geographical location. For the majority of independent spaces without the privilege of permanent premises, however, relocations are common, dictated by changing needs, shifting patronage, financial constraints, and the rental market.

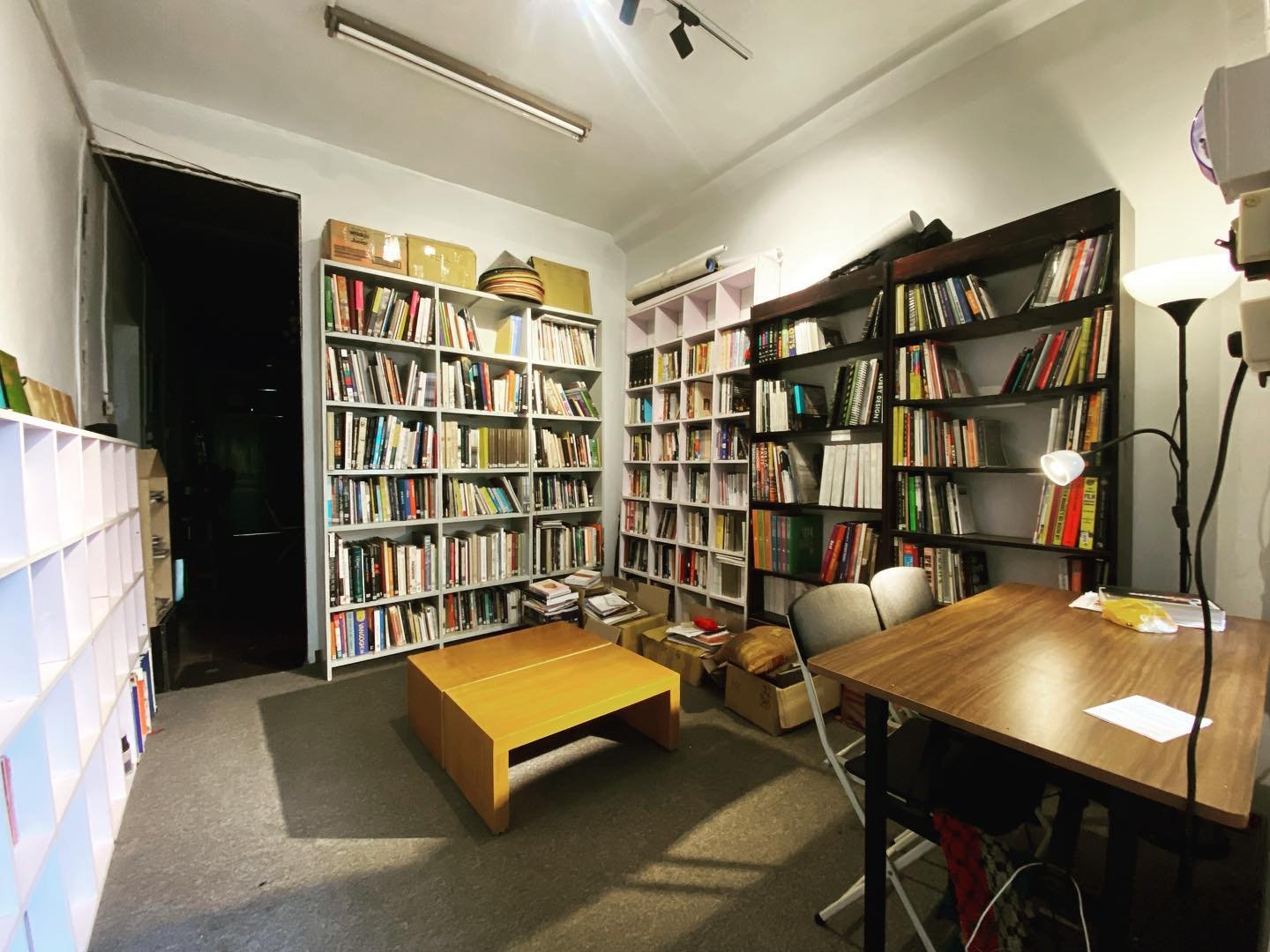

HAS has moved a total of four times in its decade-long existence. In its early years, the mixed-use complex Dolphin Plaza in western Hanoi sponsored HAS with a spacious area on its ground floor and mezzanine, which served as an exhibition and performance hall, a communal studio for HAS’s residency program, and a venue for film screenings, academic talks, and artist-led workshops. When the backing by Dolphin Plaza ended in 2019, HAS transitioned to self-financed, more modest spaces. Its first relocation was to an office at the Vietnam Institute of Culture and Arts Studies, where exhibitions could still take place in the institute’s gallery. However, impending renovations forced another move the following year, when HAS moved to the second level of a residential house shared with artist-curator-organizer collective ba-bau AIR on Thợ Nhuộm street, near Hanoi’s Old Quarter. Here, the venue served mainly as an office and an informal gathering place for seminars or artist talks. After two years, the limitation of space and difficulties with the landlord prompted yet another move, this time to an apartment on the third floor of a French-built tenement on Tăng Bạt Hổ street. Here, HAS could welcome small numbers of visitors to its library of over a thousand titles. Seeking a larger venue that can host small-scale events and accommodate more library visitors, the organization relocated once again in 2024 to its current home on the second floor of a shophouse overlooking the barracks of Vietnam People’s Army.

The challenge of securing and maintaining a physical space is not unique to HAS. Hanoi has seen multiple attempts at developing cultural clusters, notably Zone 9, where a group of independent cultural practitioners came together to transform a former pharmaceutical factory on the southeastern fringe of downtown Hanoi into a hub of art studios, galleries, boutiques, restaurants, and nightclubs. Although Zone 9 quickly became a well-loved destination for the alternative scenes, it was shut down by the authorities following a fatal welding accident.An article by The Economist suggests that the closure of Zone 9 might have been brought upon by parties with economic interests in the real estate. See M.S., “Zone 9, deep-sixed,” The Economist, January 28, 2014, ➝. Some of Zone 9’s co-founders later initiated Hanoi Creative City in a nearby building, but that never gained enough traction to flourish into a noteworthy destination for arts and culture.

These examples underscore the challenge in Vietnam for independent agents, even when acting collectively, to establish long-term spaces for artistic and cultural development. Many collectives, such as Nhà Sàn Collective that had a stint at both Zone 9 and Hanoi Creative City, have shifted to a project-based model, securing venues only when needed. For those that do manage to sustain a location in the city, their placement is often governed more by forces of the rental market than by strategic planning.

That HAS has consistently maintained a physical space, even if only a modest office, demonstrates its commitment to contributing to the local art scene in any capacity possible. Each location has distinctively shaped the organization’s programming possibilities and operational model. At Dolphin Plaza, for instance, where operational costs were high despite rental sponsorship, HAS maximized the utilization of its space by hosting a diverse range of events, from exhibitions, talks, film screenings, and workshops, to music, dance, poetry, and experimental performances. Subsequent relocations necessitated a shift to smaller-scale programming and a greater reliance on external partners for event venues and financial support. Foreign cultural institutions such as the Goethe-Institut, Institut Français, Japan Foundation, and British Council have played key roles in funding local artistic and cultural initiatives, and HAS does not operate outside this matrix. For instance, grants from the Goethe-Institut and British Council enabled HAS to launch the digital initiative Vietnam Contemporary Art Database in 2022, among other on-site events post-pandemic.

Local Concerns Meet Global Interconnectivities

From its inception, HAS’s focus has been to serve the local community while engaging with transnational issues relevant to Vietnam in collaboration with foreign experts. This commitment is exemplified by HAS’s flagship residency program, the Month of Arts Practice (MAP). Held annually since 2015, MAP brings together emerging Vietnamese artists and more seasoned international practitioners to dialogue and make new art. Public engagement is multi-faceted, encompassing specialized lectures, curatorial tours, and artist talks.

For local lens-based artist Hà Đào, who took part in the 2019 edition of MAP, the residency’s production timeline and regular check-ins—through discussions with fellow artists and curators—provided the structure necessary to develop a new work inspired by the trial of a high-profile murder case in southern Vietnam. Although the work exhibited at the end of the month-long residency was not in its final form, the opportunity to present it to a local audience was also invaluable, given the relevance and sensitivity of the subject matter. The artwork, further developed as All Things Considered (2024), has since been exhibited internationally. When an entry-level DSLR camera can easily amount to three months of average salary in Hanoi, art-making is still such a privilege in Vietnam that the little nudges that independent art spaces like HAS can provide can go a long way in advancing a budding artist’s career.According to the General Statistics Office of Vietnam, the average monthly income of an employed worker in Hanoi in 2022 is 8.858.900 VND, which is around 375 USD at the time.

Besides facilitating knowledge exchange, cross-border partnerships enable access to the global pool of funding sources. In response to a state-wide open call among higher education institutions in Germany, a long-time friend of HAS, Ingo Vetter, pitched the idea of a collaboration between HAS and the art school in Bremen on the extended theme of “alternative mobility.” This laid the foundation for MAP 2023–25 and has given rise to unique and provocative works reflecting on the flow of artistic ideas and material goods. For instance, MAP 2024 features posters that were designed by artists in Bremen, shipped to Hanoi, and attached to courier bags of local delivery bikers. Over a one-week period, these mobile art prints traveled across the city and elicited puzzlement and curiosity among Hanoi dwellers, for it betrays the common conception of art as something confined to a predetermined, static exhibition space. As such, the project not only illuminates an expanded possibility of art and exhibiting, but also the tantamount role of the logistics industry in the functioning of the globalized art world.

For HAS, global connectedness—a yardstick of development in the post-Cold War era—is not an end in itself. Historically, Vietnam has been entangled in several matrices of power, in ways that continue to shape the lived realities of its people and diaspora today. Collaborating with foreign cultural institutions is also an opportunity to critically examine these legacies. A compelling example of this is the 2023 experimental theater project The White Memorial Zone, jointly designed and run with local theater maker Hà Nguyên Long. As part of the larger project “Echos der Bruderländer” by Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin, The White Memorial Zone explores alternative modes of interrogating post-socialist links between Germany and Vietnam via material and memorial relics of former Vietnamese contract workers to the German Democratic Republic. Put another way, in a country where the state’s response to contemporary art is largely reactive rather than proactive, connecting with foreign institutions has been a key strategy for independent spaces to obtain the much-needed resources to create and sustain artistic conversations.

The Making of an Art Ecosystem

While foreign funding is appreciated, it is neither unlimited nor unconditional. Thus, co-creation and domestic partnership remain essential to the collective survival of Vietnam’s art scene. At the most basic level, it is a matter of sharing material resources, like borrowing equipment or lending event venues. When HAS had the privilege of space at Dolphin Plaza, it served as a venue partner for Nhà Sàn Collective’s interdisciplinary art program “Skylines with Flying People.” In a similar spirit, HAS later received support from artist Nguyễn Mạnh Đức to hold the MAP showcase in his studio space in the Bát Tràng ceremics village. Indeed, this tradition of giving and receiving has been core to Vietnam’s contemporary art scene since its early days, when pioneering artists opened their private homes to fellow artists, fostering communal spaces for alternative artistic practices.

Another way to look at collaboration is as a way of distributing finite funding to maximize long-term benefits for the local art community. In 2023, HAS partnered with Next Door to the Museum, an independent experimental residency in Jeju, to conduct research on the underground art scenes in South Korea and Vietnam. Among the participants from Vietnam was independent curator Vân Đỗ, who bonded with a fellow resident, writer-curator Eom Jehyun, over shared concerns in art. When Eom Jehyun later secured funding for his art criticism webzine Pong, they initiated project “Mù,” which publishes new writings on provocative issues in the practice and reception of contemporary art in Vietnam. HAS has also extended its reach within Vietnam beyond Hanoi, partnering with Hồ Chí Minh City-based collective Tản mạn Kiến Trúc to run workshops at an art school in Singapore. The topics of these workshops are specific to the southern Vietnamese cultures, such as landscaping in traditional nhà rường houses and mask design in traditional hát bội opera. Unlike other projects focusing on Vietnam’s modernist architecture in metropolises, Tản mản Kiến Trúc reckons with diverse vernacular forms in both urban centers and peripheral towns, attending to not just elements of tropical modernism but also aspects of precolonial lives. The collaboration gave Tản mạn Kiến Trúc the opportunity to explore new audiences beyond the borders and expand its operational scope.

While structured collaborations with clear deliverables are the most visible form of community-building, informal and serendipitous engagements are just as crucial. For instance, at the time when HAS and ba-bau AIR shared space on Thợ Nhuộm street in Hanoi, a HAS member donated a spare bed frame to ba-bau AIR to furnish the communal space, which was subsequently moved to ba-bau AIR’s residency space in Hoà Bình, south of Hanoi. There, Thai artist Awika Samukrsaman took the bed as a substrate for a new installation work, Geo-Romanticism (TH-VN Relation), with yarn woven through the bed frame. Seeing the piece at the artist’s open studio, HAS was inspired to feature it in MAP 2024. The bed frame thus came full circle when it was shipped back to Hanoi for the showcase, its journey embodying the very theme of mobility central to the program. Another organic fruition of HAS’s activities is the trajectory of the artist Linh San, who first encountered contemporary art at an exhibition co-organized by HAS while she was a freshman in college studying literature. The experience left such a lasting impression on her that she sought deeper involvement in art, first as a gallery sitter for HAS, then a program coordinator. Eventually she found opportunities to develop her craft and show her works with other local independent spaces, including a solo show at Á Space and group exhibitions in the region.

The case of Linh San highlights how HAS contributes to the conviviality of an art scene that helps emerging artists forge their own unconventional training and practice outside formal academic and institutional pathways. The fragility of independent art spaces also means this conviviality is subject to ebbs and flows of funding and state regulations, causing independent spaces to close down, open up, or adjust their mode of operation. HAS’s program manager, Phạm Út Quyên, borrows the term “rhizome” from Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari to describe this dynamic nature of the local art scene, imaging it as a nonlinear network of art spaces, collectives, artists, organizers. While ever susceptible to deterritorializing forces—pressures from the economy, the state, or moral norms of the domestic public—this rhizomatic system is nevertheless capable of self-healing as its nodes rearrange and new connections form to transition to new steady states. One can see this reterritorializing operation in action through Linh San, who went on to work as part of the curatorial team at the newly opened Outpost Art Organization, or Hà Đào, who worked as part of the team at photography space Matca, co-running an alternative summer photography school for local emerging photographers.

Of course, deterritorialization is not just about dampening independent practices; it also entails reshaping the art scene as new actors appear or existing ones undergo reconfiguration. In recent years, new art spaces backed by private collectors who desire a more public face or influential role in the local scene have been popping up.Examples include the Outpost Art Organization in 2022, Hanoi, and Nguyễn Art Foundation in 2018 and Quang San Museum in 2023, Hồ Chí Minh City. Meanwhile, since Hanoi joined the UNESCO Creative Cities Network in 2019, municipal authorities have shown greater interest in working with independent spaces.Since 2021, the municipal authorities of Hanoi and the Vietnam Association of Architects have organized the yearly Hanoi Festival of Creative Design, which actively enlists independent art organizers and organizations for art exhibitions, public installations and seminars. With its adaptability and resilience tested by a decade of operation, HAS is well positioned to maintain a vital presence in this evolving art landscape.