Step by Step, Dot to Dot: Building OtherNetwork through Collaboration

August 6, 2024

Editorial, Paris, Navigating Friction

August 6, 2024

Editorial, Paris, Navigating Friction

The concept of connecting independent spaces from a top-down perspective is inherently met with resistance. Friction is rooted in maintaining each space’s distinctiveness and autonomy while establishing connections that bridge them. As developers of the OtherNetwork platform, we were faced with the challenge of establishing a format for a website that doesn’t overlook the possibilities of this friction. How to cultivate a collective process that moulds an existing shared reality rather than imposing a new one? How to visualise data in a way that is collaborative, and non-extractive?

As we look at the format, functionality, and real-life iterations of this very website, it’s clear that our journey to understand it has been anything but straightforward. When we first got involved in the project it was still a spreadsheet – brimming with potential, but a long process away from the complex platform it is today. The transition from a spreadsheet to a published website was a particularly delicate process for a project still defining its identity.The preliminary OtherNetwork research team consisting of Emmaus Kimani (Nairobi), Samantha Modisenyane (Johannesburg), Lucille DeWitt (Kinshasa) and Abraham Tettey (Accra) had the primary task of gathering data collectively in a spreadsheet following an on-the-ground approach rooted in their knowledge of existing artistic networks. As the project progressed, an expanded research team consisting of Samantha and Abraham together with Mattheus dos Reis (São Paulo), Camilo Quiroga (Bogotá) and Camila Alegria (Santiago) refined their research methodologies to engage with local institutions and contacts for events and new collaborations. At different stages of the process, we were often tempted to retreat and keep our ideas for the platform confined to spreadsheet cells, rows, and columns. A format that felt familiar and almost comforting—until some uncertainties were lifted. In retrospect, remaining in this vulnerable format for what seemed too long at the time profoundly shaped the project into what it is today. Embracing this form of vulnerability and being exposed to uncertainty during the website’s development almost poetically mirrors the project’s essence.

In attempting to develop a platform that doesn’t reinforce the hierarchies and power structures that exist in the art world, finding a fresh format for data visualisation was always a priority for OtherNetwork. The most obvious proposal would have been to turn raw data into a map – a strategy that we encountered when researching some of the many precedents to OtherNetwork. However, this approach was abandoned early on for a number of reasons. To quote graphic designer Joost Grootens in his 2021 book Blind Maps and Blue Dots, “Users are blinded by the beauty of maps, or by the underlying worlds and processes to which they refer.”Joost Grootens (2021). Blind Maps and Blue Dots: The Blurring of the Producer-User Divide in the Production of Visual Information. Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers.

With this in mind, relying on traditional geographical representation proved to be too conventional, and a diversion away from the core of what the database contained. Moreover, in our case the use of a world map is too charged with history that might have threatened to sidetrack our intention to encourage participatory, local conversations and connections. Critical cartography is a distinct field of its own, with a long tradition of historical analysis examining the production of maps. Chief among these is the historical reality that authoritative entities like states and political bodies have predominantly crafted traditional maps. Geographer Brian Harley, who first coined this term critical cartography, argues that mapping has been and remains a key device in the formation of colonial projections of power and control. In Maps, Knowledge and Power, he highlighted that “As much as guns and warships, maps have been the weapons of imperialism”.John Brian Harley (1988). Maps, Knowledge, and Power, Cambridge; Cambridge University Press

In relation to independent art spaces embedded in the local contexts of many formerly colonised nations, finding a new format became one of the first certainties of the project. A world map in the traditional sense would just reveal how cultural imperialism strengthens the connections among Western institutions which continue to fund many artists internationally, rather than emphasising existing connections between artists and their local communities in the global South. Additionally, mapping on a local scale could have played heavily into narratives around gentrification, and the processes of displacement that take place when clusters of art spaces are identified and capitalised on by the property industry.

For these reasons, we looked towards alternative forms of mapping. As anarchist collective Tiqqun wrote, quoted by Geert Lovink in Stuck on the Platform: Reclaiming the Internet:

“Rather than new critiques, it is new cartographies that we need. Cartographies not of the Empire, but of the lines of flight out of it. How is it to be done? We need maps. Not maps of what is off the map, but navigation maps. Maritime maps. Orientation tools. That do not try to explain or represent what lies inside the different archipelagos of desertion, but tell us how to reach them.”Geert Lovink (2022). Stuck on the Platform – Reclaiming the Internet. Amsterdam: Valiz

Putting aside the world map format and embracing alternative orientation tools then, we were able to reassess every aspect of the platform—still allowing for navigation by country and city, but more fundamentally by emphasising connections. This shift allowed us to envision a blank canvas, fostering connections between spaces and opening up a more fluid approach that better reflects the ways that many artist-initiated projects operate. Geography is, of course, still visible in the visualisation of countries and city networks, but we hope for less defined borders.

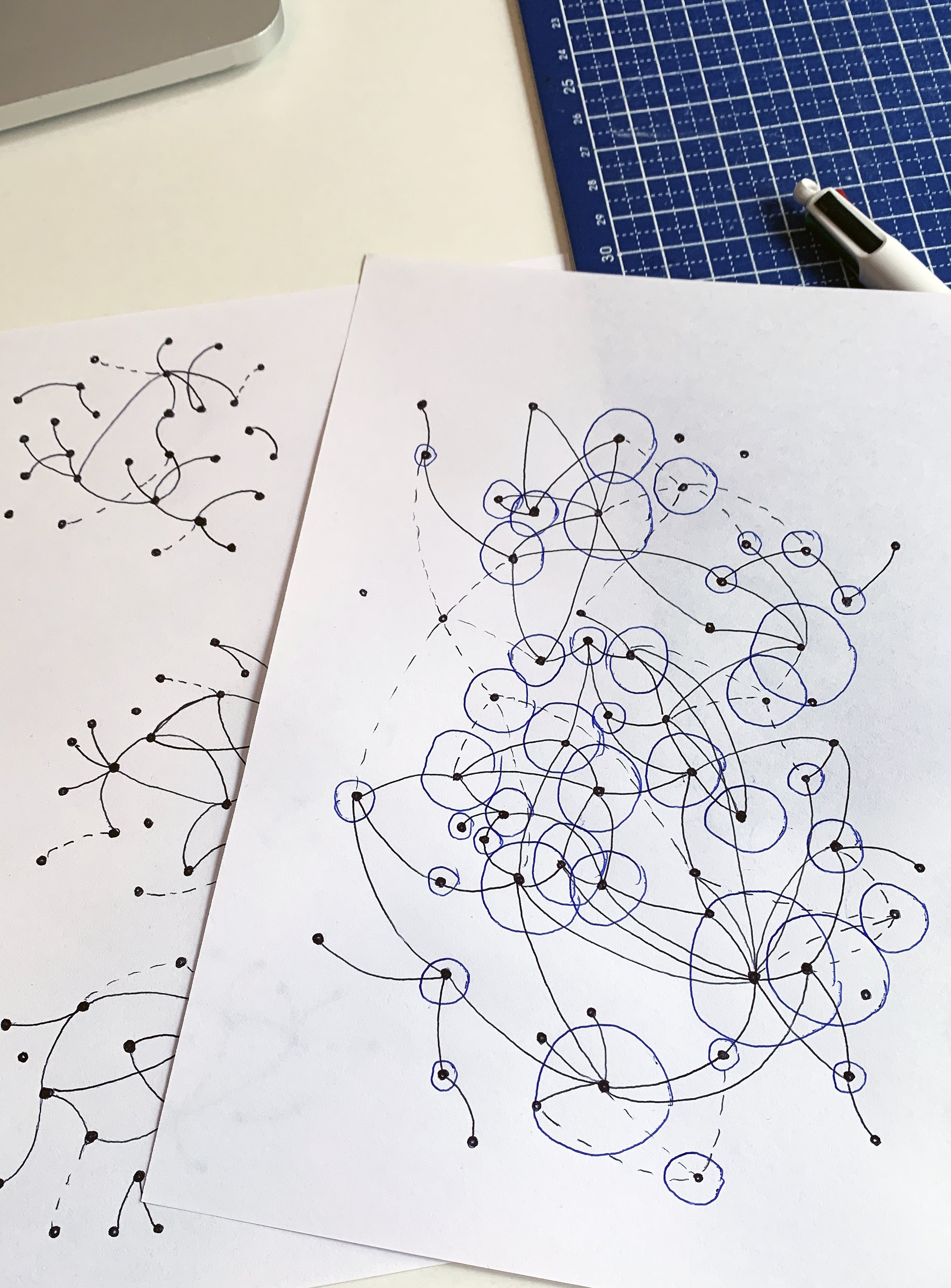

Initially, building the platform around connections was some sort of vague collective intuition that came about while we were still working in a database format. To formalise this, switching to a relational database structureA relational database (RDB) is a type of database that stores and provides access to data points that are related to one another; making it easy to see and understand how different data structures relate to each other. In OtherNetwork's database, it helped connect artists, spaces, and cities, and sort entries by different categories. This helped the team understand the data better before it was organised into a network layout. allowed us to see networks as interconnected nodes, sparking lively discussions about the countless possibilities they could bring. It was from this very moment that a network visualisation became an evident direction. However, in the same way that maps do, data visualisation also carries the same seductiveness that Grootens warns us to be cautious of. In her 2015 essay What would feminist data visualization look like?, MIT Professor Catherine D’Ignazio notes the tendency to accept visualisations as factual due to their association with scientific settings, despite their context: “Charts are accepted as fact because they are generalised, scientific and seem to present an expert, neutral point of view”.Catherine D'Ignazio (2015). What would feminist data visualization look like? – MIT Center for Civic Media. [online] Available at: https://civic.mit.edu/feminist-data-visualization.html Ironically, this ‘neutral’ point of view proved to be an intriguing foundation for OtherNetwork. By admitting and understanding the perceived neutrality of data visualisation, we gained an opportunity to approach the project with a sense of openness.

As designers and developers, we are trained to have a programmatic mindset and a systematic approach to solving problems. We often spend our time – and particularly enjoy – finding solutions and systems to answer the biggest number of questions in one defined programming script with a single set of instructions. In other words, if we can think of something that shows promise in a narrow context, the strong computer programming impulse is to scale that up to as many contexts as possible. In the case of OtherNetwork, we had to follow the opposite impulse. With a process rooted in collectively building the platform as new spaces are added as entries to the network, the project’s evolution was prompted by discussions about how it could best serve its users with focus-groups held in Accra (October 2021), Lagos (September 2022) and Stuttgart (October 2022), as well as weekly online meetings with the research team. This required a slow and cautious approach, based on digging, dwelling and leaving open questions about the functionalities of the website, which seems closer to a design research approach than a programming one. As software engineer Andy Matuschak writes in his working notes on software development:

“Effective system design requires insights drawn from serious contexts of use. It’s possible to create small-scale serious contexts of use which will allow you to answer many core questions about your system. Indeed: technologists often instinctively scale their systems to increase the chances that they’ll get powerful feedback from serious users, but that’s quite a stochastic approach. You can accomplish that goal by carefully structuring your prototyping process.”“About These Notes.” Andy Matuschak’s Notes. Accessed August 8, 2024. https://notes.andymatuschak.org/About_these_notes?stackedNotes=zKKB5ENRahwftH96H7mijiu.

By slowing the pace and creating a small-scale, meaningful testing ground, we were able to avoid freezing the conceptual architecture of the website. This approach allowed the project to evolve naturally, resisting the temptation to revert to more conventional, structured methods typical of web development.

In following this counter-impulse, we had to wrestle with the fact that the web environment is generally a fast-paced process that is pretty hostile to a research approach. This can quickly lead to discouragement when faced with problems that require a steadier pace. In today’s tech environment, it’s therefore difficult to experiment radically, as users expect a website to work perfectly and be solid proof of the concept’s validity. Unlike other disciplines, websites lack a tangible testing ground. In bookmaking, a dummy lets you experience the texture and format, while in architecture, a model helps you explore scales and material details. In web design and programming, we have what’s known as a prototype, but it’s not as well received: it’s hard for users to embrace its flaws and discontinuities. In an era where polished user interfaces and seamless interactions are the norm, navigating a prototype riddled with bugs, inconsistencies, and unfinished features can undermine the trust we place in the outcome. Bumpiness is not something you want on a website.

Additionally, before publishing a website, it must meet various standards. These include technology requirements, GDPR complianceOddly enough, the initial launch of the website in October 2021 had to occur without any content at all. We realised late in the process the need to implement a double opt-in verification system for every artist, curator, art space or other database entry, in order to comply with GDPR. This required a complete restructuring of the database, which took several months. Throughout this period, the website remained online, but without any visible content. As a result, the city networks became ghost towns, devoid of the dynamic activity the website might have presented or promised. and performance issuesThe initial prototype functioned smoothly on local hosting. However, extending its accessibility to the OtherNetwork team, situated in different regions worldwide with occasionally not-so-stable internet access, became a challenge in terms of website performance. This workload, typically encountered towards the project's conclusion, required work and optimisation efforts at the beginning of the project. For example, the database connections were initially limited to entries and cities, with dynamic city connections for the homepage. But with over 2000 entries, managing loops became impossible, causing homepage loading issues. We had to add city connections, leading to complex back-end operations for entry management.. Each of these tasks is quite time-consuming and requires careful attention before attempting to share the website. It was particularly obvious for othernetwork.io that these protocols and standards impacted various defining moments of the platform. Looking back, it’s hard to say when OtherNetwork was truly published. Was it when the database was first shared? When we bought the domain name? When the content took on a structured format? Or perhaps when it was first used by users? In a way, OtherNetwork was never formally published; it has evolved through the aggregation of ideas, collaborative development, and the use of tools to adapt them.

In materialising some intuitive aspects of OtherNetwork, we had to balance proving the concept for a large context of use cases as well as smaller, more specific contexts. While technology offers convenient solutions for widespread scenarios, it became important here to resist the temptation to prioritise that and instead stay focused on our core values: small-scale. One of the former contexts was the city of Accra. In a way it served as the initial testing ground for the platform, allowing us to refine and define its features. Through an exploration of Accra’s artistic landscape, we discussed the need to prioritise connections—both digital and real-life—within local networks.

When navigating Accra’s city network on the website, one can’t help but notice the remarkable ratio between individual artist hubs and collective spaces. What’s particularly intriguing are the connections; each individual dot seems to link to other artists, almost forming micro-communities of their own. This dynamic was not just observed but brought out during discussion with Abraham Tettey, Ato Annan and Adwoa Amoah during the first stages and uses of the platform. This first observation was cultivated through a variety of local events, such as Community, Generosity, and Longevity: Strategies for Independent Cultural Production in Ghana, or at the opening of the exhibition Delay and Encounter and/or Other Proximate Unknowns. Accra revealed the need to prioritise connections—both digital and real-life—within local networks. It allowed for insights to be gained through making, yes, but also through gathering. Here, the meaning of gathering as positioned by designer and researcher Mindy Seu resonates deeply with the underlying process of building community and the collaborative platform that OtherNetwork aims to evolve into.

“Gathering is, in this way, not the act of aggregation alone. It is not an automated collection or the formal acquisition of works for an institution, nor is it the plundering or extraction of resources from a neighboring region. It is the tender and thoughtful collection of goods for your kin, and a moment for reunion, for celebration, and for introspection around those goods.”Mindy Seu (2022). On Gathering, Collecting, sharing, and creating the Cyberfeminism Index. [online] Available at: https://issue1.shiftspace.pub/on-gathering-mindy-seu

As we continue to build OtherNetwork, we aim to foster connections, collaboration and a sense of belonging in alignment with both definitions of gathering – not merely by collecting data, but also through moments of reunion. Our focus is on maintaining an open-ended approach to the platform’s future. We aim to let the project evolve organically, steering clear of unnecessary technological complexities that could get in the way of our cherished discussions and reflections. We see this website as a draft, a forever work-in-progress rather than a polished, finalised digital artefact.