The Parasite: Data and a Chorus

July 30, 2024

Editorial, Bogotá, Navigating Friction

July 30, 2024

Editorial, Bogotá, Navigating Friction

In this article, I appropriate, deform, summarise and rewrite passages from The Parasite (1980) by Michel Serres. I not only chose this book due to its experimental nature and its dissimilitude to conventional academic writing, but also because even though it is now deemed to be a major post-humanist work, it uses fable to explore the ways in which human and non-human relations are similar to those of a parasite and its host organism. Serres argues that by behaving like pests, minor groups can become major players in public dialogue and hence give rise to diversity and complexity, which are vital to human thought. He also claims that ideas like independence, autonomy and agency conceal human beings’ interdependence with their environment.

The argument from Serres that I find the most compelling when considered in relation to independent spaces in Bogotá is his suggestion that a parasite is a key feature of any system, acting as a “thermal exciter” that alters the nature of the environment to which it belongs. The independent spaces within Bogotá’s art scene have acted as parasites in this sense, as opposed to the commonly construed notion of an organism that lives off others, feeding off and decimating them, without actually killing them. Serres tells us to take a closer look. For him, a parasite is not so much a drain on the energy of a system but something that changes the very nature of the host. When seen in this way, Bogotá’s independent spaces have acted as the parasites of the local art system, as catalysts that have galvanised an art scene in the grip of commercial control.

This is a twofold article, with two melodies or separate texts, if you prefer: one consisting of information, and the other acting as a chorus. The first outlines the characteristics and evolution of the spaces regarded as being independent within Bogotá’s cultural scene.Most of the information comes from a review of the “Yellow pages” section of the book Por las galerías, atlas de galerías y espacios independientes, Bogotá 1940 – 2018, which I published in conjunction with José Ruiz and Natalia Gutiérrez Montes. It describes how they developed geographically to form today’s art networks; that is, clusters of spaces close to one another. The other part, in the form of a chorus, is rather like a sounding board, built up through quotes weaving together appropriations from Serres’ book with phrases uttered at an event hosted by OtherNetwork at Espacio Odeón in Bogotá on July 13th 2023. The participants’ voices relinquish their authorship in this parasitic secondary text, uniting to form a chorus consisting of fragments of Rafael Díaz, Tatiana Rais, Juan Sebastián Peláez , Andrés Moreno, Jenny Díaz and Valeria Giraldo. To interlink these voices, I appropriate a phrase from the poem “El sueño de las escalinatas” [The Dream of the Stairs] by Jorge Zalamea, which does none other than prompt the creation of a chorus.

I: Centro-La Macarena

Bogotá’s very first known art gallery was paradoxically called Galería de Arte [Art Gallery] in forthright, simple style. It opened its doors in 1940, run by Ukrainian anthropologist Juan Friede. Competitions, raffles and tombolas were held there to dynamise the art market. The gallery’s business card from back then bears the words “Permanent sales of paintings, sculptures and art objects. Consult our office for prices.” The gallery was in the city centre, at the intersection of Avenida Séptima and Carrera 23, close to where Terraza Pasteur shopping centre now stands in Santa Fe. In the mid 20th century, when the city’s historic centre had come to integrate places like Teatro Colón, Teatro Odeón and the Museo del Oro, this area was Bogotá’s main cultural hub.

Ten years later, in 1950, Barranquilla-born artist Orlando Rivera – affectionately known as Figurita – arrived in Bogotá. He wanted to hold an exhibition of his latest work, but had neither institutional backing nor a place to host it. In the old quarter, in addition to the city’s cultural hot spots, there were cafés in Avenida Jiménez where intellectuals, writers and artists gathered. According to journalist Fernando Jaramillo, when a worried Figurita came to his café, wondering where he could possibly exhibit his work, Jaramillo told him “Well, hang the paintings here and let’s see what happens”. That was how exhibitions first came to be held in El Automático café.

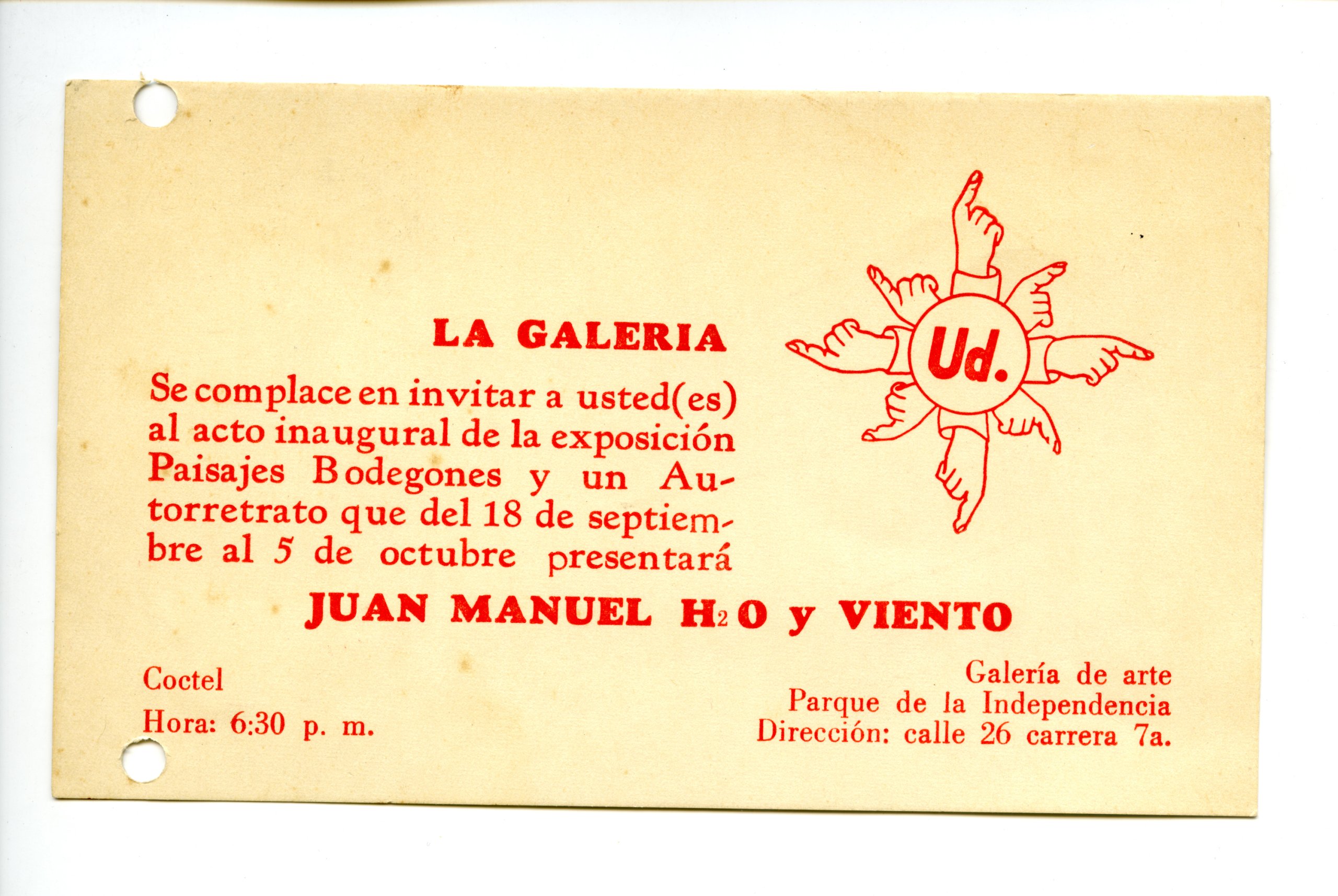

Not far from there, walking north up Calle 26, Galería Gasquet was founded in 1961 in the building of Tequendama Hotel. Close to the hotel, in the 1960s, was Galería del Parque, housed in Templete de la Luz, a folly in Independencia Park. In this same folly in 1967, Matilde de Lewental, Raúl Marroquín, Clemencia Lucena and Luis Fernando Lucena founded what was perhaps one of the first artist-run galleries in the city, Galería Ud. It opened on September 18th that year with a solo exhibition of work by artist Juan Manuel H2O y Viento. The gallery was “solely devoted to exhibitions of paintings by young Colombians, who have always found it very hard to exhibit their work”, as announced on the leaflet of the first exhibition there. It is intriguing how support for young artists (who often lack platforms to show their work) has acted and perhaps will always act as a driving force behind the creation of independent spaces in Bogotá. Like many others, this space in particular aspired to act as a bridge between the public and younger artists and to show “that work by Colombian artists is serious, important and indispensable, and not just a luxury item,” in the words of Clemencia Lucena in an article published in 1968 in Issue no. 3 of Art-Pía magazine, on the subject of the first anniversary of Galería Ud. In this area, close to the Museum of Modern Art Bogotá, La Macarena network of art spaces would gradually develop.

The audience grows and grows: Let’s begin. What is a parasite? To parasitise means to eat next to. Let’s start with this literal meaning. The country mouse is invited for supper by the town mouse, much like when a gallery invites an independent space or when an independent space is given a stand at an art fair. The essential thing, one will say, is their relation, resemblance or difference. A parasite is guest and host. But that is not enough, has never been enough. The relation of being the guest will soon no longer be so simple. Giving or receiving, on the tablecloth or on the carpet, passes through a black box.

Parasitism is a symbiotic relationship. Above all else, symbiosis is an interaction and the development of a link. What is living together? What is collective? What if the system in question were a collective? What relations do we really have with one another? How do we live with one another? What is that system that collapses at the slightest noise? Who or what makes that noise? Who or what prevents me from hearing whom, from eating with whom, from sleeping with whom? How can I love? Who receives whom? Who should I love? Who could I love and who will love me? Who forbids love? Is this noise both the collective noise and the sound that comes from the black box? A parasite is both guest and host.

The terms ‘independent’ and ‘autonomous’ have been discussed in the field of art, particularly in Bogotá, with connotations of heroism, because the independent and autonomous spaces have been called to do what Institutions – with a capital ‘I’ – cannot or do not wish to do. The independent spaces take in the young, providing an exhibition space for those lacking one. The independent spaces are instigators. But independent from what? From whom? Why are they called independent? For a Parasite, independence is not isolation or separation, but the capacity to function in a system of relations without being dominated or subjugated by other elements of the system. It is a balance between giving and receiving, influencing and being influenced. For a Parasite, autonomy is the capacity for self-governance in a system of relations. Autonomy does not negate interdependence; it accepts it as a fundamental condition for it to exist.

II: La Macarena - Chapinero

Galería El Papi Hippie was a gallery founded in 1968 as part of the Papi Hippie movement, which emerged in Bogotá in the late 1960s. It was founded by a group of friends including Pierre Tack in order to “try and forge links between plastic art and music”, in keeping with the ideals of American hippie movements. The gallery stood in Calle 85, in the Chapinero district, nine kilometres from Galería Ud., where plans for the first space for young artists in the city had been hatched. Galería El Papi Hippie was possibly the first independent space in Zona Rosa, an area of the city where several galleries can now be found. Twenty years later, the legendary Valenzuela Klenner Galería would open nearby, at the intersection of Calle 84 and Carrera 13, on the second floor of a bar, before later moving to a residential neighbourhood. It had a distinctive spirit, seriously committed to exhibitions of contemporary art in dialogue with local issues, without following any particular commercial formula. It set its sights on young artists, although it was also a space for artists like María Teresa Hincapié and José Alejandro Restrepo at a point when they could not find a place to exhibit their work. In 1995, the gallery moved to La Macarena, although it was finally forced to close during the Covid pandemic.

It is important to note that during this period, galleries (and the whole of Colombia) were immersed in a serious crisis, and the artistic climate had soured substantially. The influence of the drug trade had generated strong mistrust in the art market, and the conventional model of an art gallery had been called into question. This led to a number of experimental independent spaces, including Magma, Gaula and Espacio Vacío. Magma opened in 1985 in a house at the intersection of Calle 67 and Carrera Sexta in the Chapinero district, unfortunately on the same day as the national tragedy of the Palace of Justice siege. It was founded by Jaime Iregui, Rafael Ortiz, Marta Combariza and Paige Abadi, who sought to galvanise the art scene outside the network of trend-setting commercial galleries, where artists of the time were given a stamp of approval. On the second floor, there were studios for each artist, while the first floor featured an exhibition area and a crèche for children. Programmes of films were organised, and there was an art shop. Magma was not interested in selling works of art, but in being a communal area with studios and a place to show art by residents and guest artists. With time, their enthusiasm waned: it was hard to keep up with rental payments, and in 1987 they decided to close.

Following the closure of Magma, Gaula was created in 1991, based in a workshop in La Macarena, although it closed only a year later. It was a prime example of an artist-run space, conceived as an exhibition venue for the artists that ran it: Jaime Iregui, Carlos Salas and Danilo Dueñas. It was an anti-commercial space, albeit based on a commercial structure, since the idea was to sell work. Irequi, Salas and Dueñas wanted to accommodate projects by other young artists, making no concessions to the way work was exhibited.

Espacio Vacío was on the first floor of a three-storey building built by Carlos Salas in Chapinero. It opened its doors to the public on February 7th 1997 and closed in 2002. There was no opening exhibition, nor was it based on any specific kind of art space. The opening was more of a symbolic act, presenting the empty space with no work on its walls as an invitation for artists to come up with proposals for projects or experimental processes. It was here, on Sunday May 7th 1997, that artist María Fernanda Cardoso exhibited her Flea Circus, with over 300 trained fleas performing juggling, trapeze and dance acts.

The audience grows and grows: We know of no system that functions perfectly; that is to say, without losses, leaks, erosion, errors, accidents, opacity; a system whose profit would be one for one. What do you consider an independent space to be? It changes with the context, place and time. Something that was thought to be an independent space ten years ago no longer is. Ten years ago, a project that didn’t fit in with certain commercial dynamics clearly seemed to be an independent project. But, independent from what? These spaces are reliant on a lot of people, on an ecosystem, on infrastructure. Nothing is independent. Today, we use the word independent (a term that appears to have been coined in the 1990s) to refer to an attitude of not fitting in with the system, of being anti-market, of mistrusting official institutions, or of the need to be parainstitutional as opposed to anti-institutional.

III: Chapinero–San Diego–Teusaquillo–Bosque Izquierdo

Independent spaces in Bogotá often spring up when people leave university. Such spaces become a sort of obligatory port of call, a rite of passage where people can meet up and form a community. Casa Guillermo was a space and a student collective formed in response to the sale of Guillermo Wiedemann’s house in the Chapinero district. The house had been donated by the artist to the University of the Andes’ Art & Textiles Department, and run by the university from 1988 through to its sale in 1998. A group of students—among them, Renato Benavides, Fernando Pertuz, Javier Ruiz and Diego Benavides—began to invite other artists to Casa Guillermo while also carrying out their own projects there. On June 15th 2000, Johanna Arenas and José Fernando Navarro (two artists from Jorge Tadeo Lozano University) who were interested in exhibiting and promoting work by young artists and recent graduates, founded Sala de Espera, also in Chapinero.

Mar Galería-Taller was an independent space founded in 2001 by Colectivo Mar (Muchos Artistas Reunidos), made up of Mauricio Gutiérrez (ArtIs) and Rafael Sánchez. The first exhibition by Colectivo Mar was held at Teatro Bogotá, a porn cinema in the city centre, before moving to a permanent location close by, on the second floor of a building occupied by several other collectives. This was an artist-run initiative where emerging artists created their own exhibition space, focusing on issues like censorship or the exploration of sexuality and the body. It made a key contribution to Bogotá’s alternative cultural scene by providing a space for artforms including comic books, fanzines, experimental video-making and music to exist. Exhaustion led to its closure in 2005, and Andrés Frix, one of the people responsible for running it, opened Espacio 101, also in the city centre. Espacio 101 was a project focused on exploring and producing fanzines as an alternative way of raising the visibility of artists and their artwork. Cara de Perro Sonido Visual was one of its forerunners, a project started by Andrés Frix Bustamante in 2002 and later integrated in Galería Mar and Colectivo Frix 2713, made up of Iván Olarte, Lorena Espitia and Frix himself, through to 2005. Espacio 101 later mutated into Salmón Cultural, which, in turn, closed in 2009 after an illegal raid by agents from the Departamento Administrativo de Seguridad (DAS), Colombia’s intelligence service.

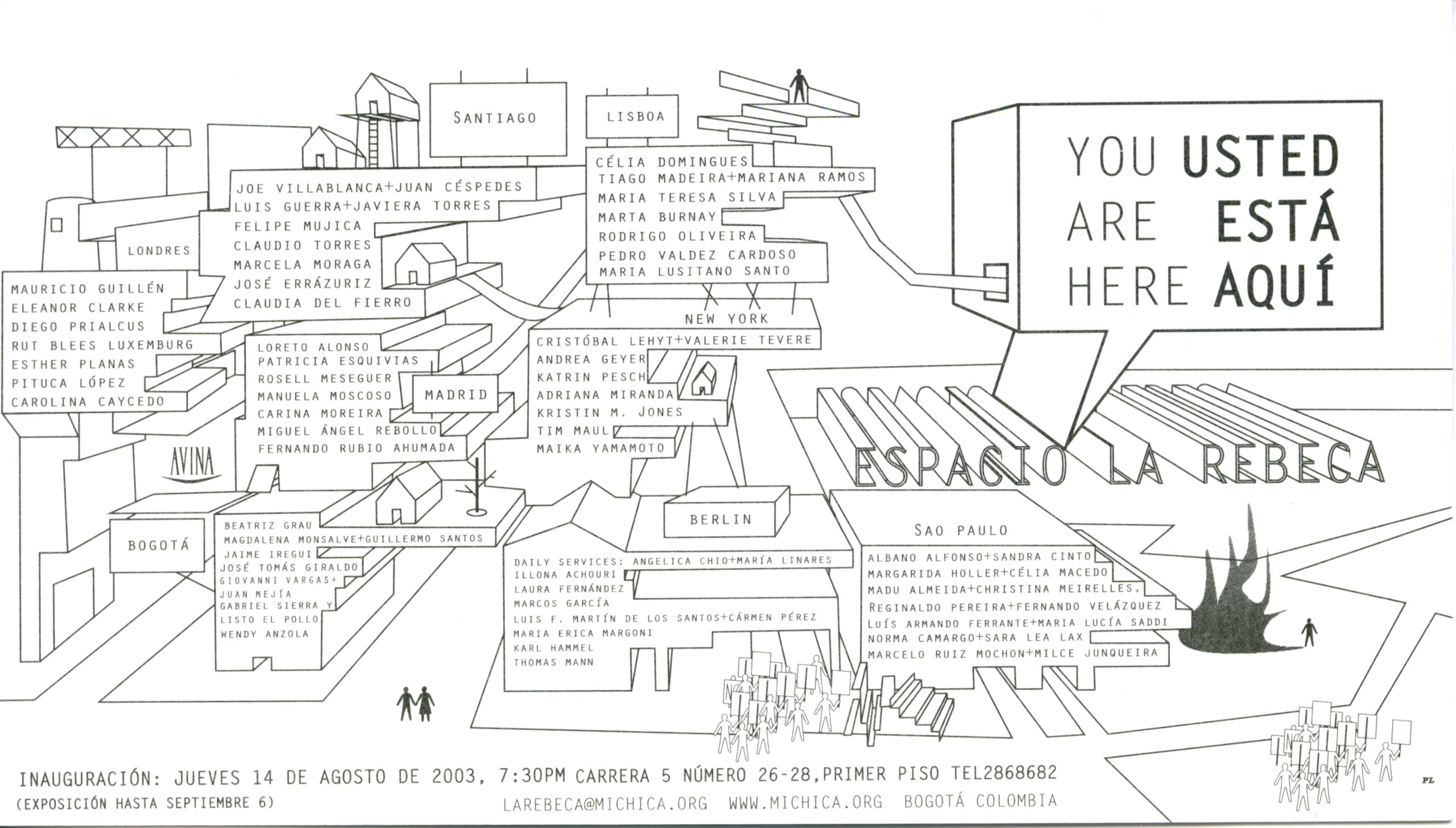

El Parche was founded not far away in January 2002, aiming to provide a space for exchange among different members of the art scene. It was located in the garage of a traditional house in the Bosque Izquierdo district, whose rooms were used for artist residencies to carry out site-specific projects tied to the local context. El Parche did not sell art, but was promoted as a platform for the visibility of artists and projects, and to build bridges between artists and possible collections. That same year, just six months after its creation, El Parche closed. When the group split up, they reached an agreement for Michèle Faguet – who had previously been the curator of La Panadería in Mexico – to keep the grant that had been awarded to them by the Avina Foundation and to use it to open Espacio La Rebeca, an independent non-profit project based on the first floor of Galería Valenzuela y Klenner. This opened to the public in August of the same year with an exhibition entitled “Arresto de Cristóbal Lehyt”. Other exhibitions held at Valenzuela y Klenner’s ‘parasite’ space include “Adiós pues” by María Margarita Jiménez, “Lovera/nascimento” by Video Ediciones-Inserciones, and “Colegiala en cinta” by El Vicio Producciones. Later, La Rebeca relocated to a traditional house in Teusaquillo that included a studio space, where it opened its doors to daring initiatives and projects from a selection of emerging artists and filmmakers from both Colombia and abroad.

In 2003, Lonely International Gallery opened, founded by El Vicio Producciones, a collective made up of Richard Decaillet, Santiago Caicedo, Carlos Franklin and Elkin Calderón. According to artist Paulo Licona, due to the similarity between the typography and pronunciation of Lonely International and Only, a chain of clothing stores with one close to the gallery, they were forced to change the name to Ganga International Gallery.

In April 2005, Espacio La Rebeca closed with the exhibition “Quisiera que estuvieras aquí” [“Wish You Were Here”]. One determining factor in its closure was insecurity in Teusaquillo and threats by criminal gangs. During its few years of existence, Espacio La Rebeca played an important role in the progressive emergence of alternative spaces in Bogotá, and influenced later initiatives on the local scene. Projects like Gaula and Espacio Vacío might be regarded as the grandparents of El Parche and La Rebeca, who in turn became the parents of El Bodegón and subsequent spaces like MIAMI, Paraíso Bajo and Laagencia. All of them explicitly or implicitly embraced the expression ‘young art’ to refer to the artwork coming from a specific generation.

The audience grows and grows: That is the meaning of the prefix ‘para’ in the word ‘parasite’: it is beside, it is next to, it is shifted; it is not the thing itself, but defined in relation to it. It has relations, as they say, and makes a system of them. A parasite is also a guest, who exchanges its talk, praise and adulation for food. A parasite is also noise, the static in a system or interference in a channel. When we do not understand, when we defer our knowledge to a later date, when the thing is too complex for the means of the day, when we put everything in a temporary black box, we prejudge that it is a matter of a system. When we finally open the box, we see that this box functions like a space of transformation. There are no systems, instances or substances except for our own ignorance. A system is non-knowledge. The other side of non-knowledge. Non-knowledge has a chaos side and a system side. Knowledge bridges these two riverbanks. Knowledge as such is a space of transformation. The entire question is fractal.

IV: Las Aguas–Chapinero–La Candelaria–Teusaquillo–Las Nieves.

(San Felipe is yet to exist)

In mid 2005, a few months after La Rebeca closed down, twelve university students and lecturers who were attached to different art faculties in the city met to create El Bodegón (Arte Contemporáneo-Vida Social). El Bodegón – the venue of numerous parties and exhibitions, based in a warehouse in the Las Aguas district – came to play an iconic role as an independent space in the first decade of the 21st century, paving the way for what would come later. It closed down in 2009, but there were other projects on the horizon.

In 2010, Laagencia [The Agency] unexpectedly came into being when one of a group of friends from the University of the Andes’ Art Department exclaimed “Let’s do something here!” in reference to the first floor of a building of workshops and offices in the heart of Chapinero. This office for art projects and experimentation featured an exhibition space until 2013. Today, its activities include educational projects such as the Escuela de Garaje [garage school], performative conferences, banquets, and relations with the non-human in the fermentation of food products.

Around the same period, Espacio Odeón was created in 2011 as a contemporary art space. It breathed new life into an old theatre by transforming it into a cultural centre, linking up with the network of other cultural venues in Bogotá’s historic centre. For ten years, it had a programme of exhibitions that included projects hitherto unseen in the city, as well as its own independent art fair. Today, Odeón is a strange case of meiosis, having since divided into several offshoots. The main one is Espacio Comunal, a programme of activities held on the first floor of the building including talks, parties and cooking. It seeks to bring artistic practices into contact with the public, exploring processes associated with the body and memory, allowing others to parasitise it while also parasitising itself through fragmentation. It allows various different collectives to use the space for their own projects and ephemeral exhibitions, including DD/MM/AAAA and Otro Espacio.

In the city centre not far from Espacio Odeón, La Redada was founded in 2011 under the slogan “Make it real”. MIAMI was created the same year by Gabriel Mejía Abad, Adriana Martínez, Daniela Marín, María Paola Sánchez and Juan Sebastián Peláez in a house in the Teusaquillo district. This space, which was originally a studio and meeting point, functioned for ten years. La Quincena, also in Teusaquillo, opened on April 26th 2012 with an exhibition of work by two of its founders, Juan Manuel Blanco and Santiago Castro, consisting of a series of paintings on unconventional media. This artist-run space had an exhibition area solely for young artists.

El Mentidero was founded in 2014 by Paulo Licona. It was a space for plastic experimentation directed at art students and young artists, originally conceived as an offshoot of the Mercadito & Mentidero project, which sold low-cost artwork, literature and cultural products. El Mentidero closed with the event “Bye Bye, nos largamos, hasta nunca” [“we’re leaving, see you never again”], held in Salón Colombia.

Más Allá is an artist-run space, headed by Rafael Díaz since 2014. The Ratus Ratus project combined studio space with exhibitions, and was run collectively by a group of friends and art students who were about to graduate from the University of the Andes. They took over an apartment where they could write their theses, work on personal projects and hold joint exhibitions. Más Allá continued that ambivalent dual function of studio and exhibition space. It has entered and exited the dynamics of the art market, playing at intermittence: at being active and then absent. It takes advantage of the ebb and flow of things, adapting depending on the way the wind blows. It is one of the oldest independent spaces on the Bogotá art scene out of a pure urge to keep going, to keep an eye on things, and not to go under. And it has stuck to one principle: to let artists do what they want, to let them have a space and an opportunity to play around and to experiment.

The audience grows and grows: The parasitic relation is the atom of our relations. Let’s try to see this face to face, like death and the sun. This blow hits all of us together.

In biological organisms and in human collectives, the parasite lives from, through, with and in the host. It could kill it, but has no interest in the host’s dying since it feeds on the latter. To avoid the hostility of the host, the parasite camouflages itself, imitating certain recipient cells and managing to make itself invisible. In this way, the parasite does away with individualisation. The parasite holds sway, because it occupies the medium and it mediates in the relations it intercepts. The one who was the guest becomes the interrupter; the one who was the noise becomes interlocutor, the one belonging to the channel moves to being obstacle. And vice versa.

V: San Felipe and Everywhere

When a network of art spaces starts to form in residential areas, this often leads to gentrification, pushing out the original local residents and replacing them with new ones, while also transforming the socio-economic fabric and the function of these urban areas. San Felipe – a district in Barrios Unidos between Avenida Caracas, Carrera 24, Calle 80 and Calle 72 – can be understood as a clear example of this kind of urban change in action, having recently been christened ‘Bogotá Art District’ due to its high concentration of galleries. KB Espacio para la Cultura is a collectively run space operating in San Felipe since 2015, that acts as a café, night club, bar, venue for parties and forum for local contemporary art activities.

Apartamento, in Siete de Agosto, and Madrastra, in the city centre, opened in 2023. They are not interested in grants or in cultivating useful contacts. What is more, Madrastra is not even on social media. To see the exhibitions you have to make an appointment in advance.

Alongside this, there have been a number of recent projects without a fixed base, taking on a different relationship to the city altogether. Paraíso Bajo was an art collective with no fixed headquarters, made up of three women – Daniela Silva, Daniela Gutiérrez and Mariana Jurado – who curated exhibitions and parasitised spaces between 2016 and 2018. Similarly, Cachorra was founded in 2021, also without a specific base. It had one clear mission: to organise exhibitions of work by artists of all ages who had never had a solo show. To do so, it acted as a parasite within Casas Riegner Gallery, before later taking over a commercial premises for a year, in late 2023, in an alley in Lourdes, Chapinero.

Otro Espacio was founded in early 2023 by María Mercedes Salgado and Andrés Moreno. They hold monthly exhibitions and do not consider themselves to be an independent space, since their motivation is to sell artwork to pay their bills. At present, they are parasitising Espacio Odeón, and throughout the year, their tentacles have stretched to various different places.

Venga le digo is another parasitic collective with no fixed headquarters, founded in 2021 and led by Jenny Díaz. It seeks to forge links outside art networks; for instance, with local shops. It is interested in ephemerality, the possibility of mutation, expiration, and in how to parasitise institutionality. Because it has no base, it is easier for the project to accept that one moment it exists, and the next, a new phase begins…

The audience grows and grows: It can be dangerous not to decide who is the host, who gives and who receives, who is the parasite and whose table it is, who has the gift and who has the loss, and where hostility begins within hospitality. Antonio Caro said they were anti-commercial, but they wanted to sell and so to do that, they programmed exhibitions of work by young artists.

Epilogue

“The parasite is invited to the table d’hote; in return, he must regale the other diners with his stories and his mirth. To be exact, he exchanges good talk for good food; he buys his dinner, paying for it in words. It is the oldest profession in the world. Traces of it are found in the oldest documents. There are a thousand known variations on this law of justice – rarely simple and often complicated – practised in social, friendly, tribal, and familial everyday life, just like in the oldest comedy or the most recondite story. For example, the sponger pays in morals and the host gives, filled with guilt by this great yet imaginary duty. The moral is one discourse among many, some sort of specie that is legal tender. Each society allows a linguistic specie that can be exchanged advantageously for food. Influential and powerful groups are able to diffuse a forced lexicon in that way. Today it is economic, just as it was humanist not long ago, Voltairean before that, and religious a long time ago.”Serres, Michel. The Parasite. Translated by Lawrence R. Schehr. Introduction by Cary Wolfe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Translated by Rachel Waters. English translation has been edited for clarity.